Below is a number of lessons I’ve learned over the year while involved in a few startups. Take note that all of the advice is highly subject to the exact circumstance.

When doing a startup, one of the first things you’ll need to sort out is this little thing called the “Cap Table.” If you’re planning for success, these numbers will work for you and against you at different times. It’ll have the ability to help propel you forward as a team or put an emergency brake on your growth and actively work against you.

As you go through capitalization events or even exit events at later stages of your company, these numbers will be a source of many conflicts and sleepless nights, which will slow you down and take your eyes off the ultimate goal. I’ve tried to capture some of the things I’ve learned over the last decade regarding cap tables and equity and the pitfalls that others can hopefully avoid.

Cap tables are really difficult to get right, and they carry unimaginable amounts of inertia with them. Once your cap table is in place, it can become a painful experience to correct it if needed. It may require lawyers, accountants and have tax implications.

As you then grow, your cap table will have implications on your founding team’s dynamics, subsequent hires (Assuming they will be offered options), and the ease with which you can go through funding rounds.

Founder dynamics

As you start, you will likely have co-founders. They will be both a key to your success and is a risk. You will get to know your co-founders exceptionally well, and your relationships will likely change dramatically. Founding a company with somebody shows you their character, which can strain relationships. Starting a company with someone you consider a friend is risky, as you may lose both the business and your friend.

Multiple things are likely to happen throughout your first year or two:

- The workload between founders will shift, and some people will pull more of the weight.

- People may realize that a startup is not for them, and they will want to move on to something else.

- The skills needed to make the company successful will change, and a founder may not be a good fit anymore.

- Interpersonal conflict will arise, leading to founders no longer seeing eye to eye.

You must be up-front and honest with each other as dynamics change and be nimble in correcting these issues. Ignoring these issues will increase the inertia, and you will have a far harder time addressing them.

Set clear expectations with everybody about what they are contributing, and be explicit about how this connects to the equity. Don’t beat around the bush if tension starts to build. There is nothing more damaging to a startup than a founder who’s not 200% behind the company and not addressing that swiftly.

At this stage, you have to be extremely careful about how you frame and discuss equity. Do not EVER discuss in terms of %. Doing so will set you up for a lot of conflict and entirely miss the point of equity.

Early hires

With your founding team in place, one of your major inflection points will be as you start to hire your first members of your team. The right hire will kick off your launch into orbit, while a mediocre hire may stall you into the ground. Between the founders and early hires, the culture of your company will start to take form. The subject of culture is not something to be taken lightly.

These early hires should receive equity options (Or whatever form it may take). There are multiple philosophies that people use to structure their equity program. And the reality is that how you utilize equity as a part of a hiring package will likely change over time.

| As compensation | As retention |

| Early on, you are likely not able to offer a competitive salary. Thus, it’s common to provide generous equity options to early-stage employees. | Later on, as you can offer more competitive salaries, you will likely shift from using equity options as a retention mechanism rather than a way of compensating people. |

At this stage, it becomes imperative that you do not discuss equity in terms of percentages. People will always try to evaluate themselves against others based on their %. A single number like that does not have any means of capturing all of the variables that go into it, and you will have people who will end up demotivated by seeing a small percentage, even if that small percentage represents a large amount in absolute terms.

Do not entertain questions around “Why do I have X% when person Z has Y%? I contribute more to the company and should have a larger %!”. Nothing good comes of it, and it can ruin morale faster than you can say “I quit”. Be sure to educate your hires about how equity works, and how to understand it. Consider explaining how the numbers were reached.

If you do not fully explain everything to people, or do not manage to answer all questions people may have (Or be willing to voice), people will fill in the blanks. And they’ll likely read into things with a negative slant, not giving you the benefit of the doubt. You’ll often see people think you’re trying to screw them over, when in fact they may have been offered a generous set of options.

Growing the pie

Ultimately, everybody should be working towards the same goal: Growing the proverbial pie, and make the company a startup. The pie metaphor here becomes very important. As already mentioned a few times, do not talk about equity in terms of percentages (Here, the exception is with VCs who understands how this stuff works).

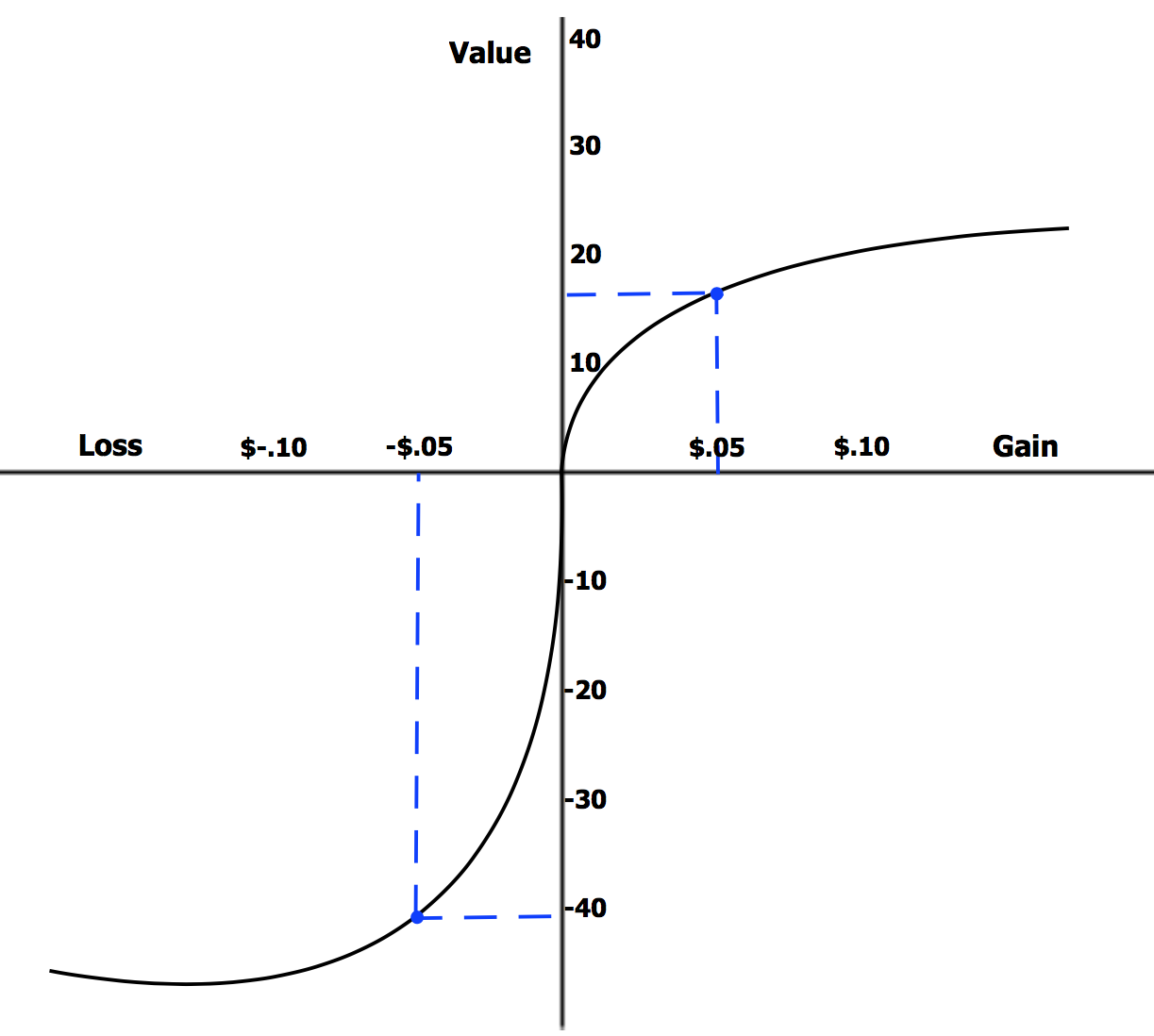

It’s important to keep people away from the simplest of instinct when looking at a cap table, which is to compare their % of the equity relative to others, and look to maximize their future potential windfall through have a larger slice of the pie, rather than growing than simply growing the size of the pie. This instinct is wrong and dangerous.

In my humble opinion, having the right people, motivated correctly, are one of the keys to success for most companies. Equity will play a big part in allowing you to bring on people and keep them motivated, and in it for the long run. It’ll also make the journey much more fun.

As such, you have to be vigilant in avoiding the instinct to not want to dilute the cap table in order to bring in more people. People will often take dilution as to mean that something is being taken away from you (I.e. percentages of the company). Giving into this instinct can really be shooting yourself in the foot.

Avoiding the shrinking of the pie

Here’s where the pie metaphor starts to really go bad. The reality is that equity is not an inert representation of (future potential) value. Especially in early phases, having “dead equity” is an existential threat. Take the scenario of a founder leaving. If they are not bought out, you will have a significant portion of “dead equity”, where the owner does not contribute to the success of the company, but will reap the benefits in the case of a liquidity event.

A number of things could be done with the equity:

- Bring in investors

- Reinforce key stakeholders against dilution down the line

- Hire new people, and granting them options

- Bring on outside advisors

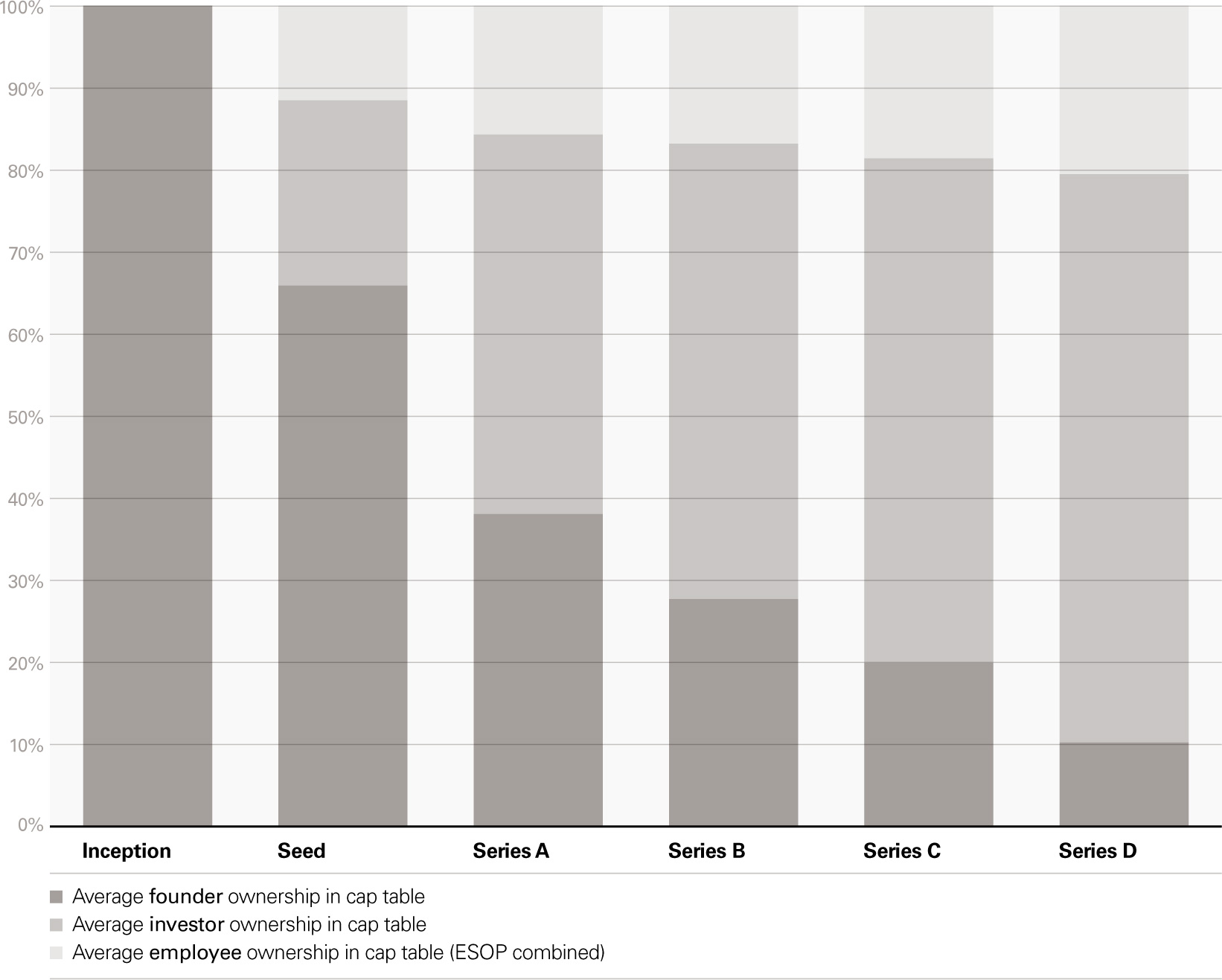

VCs are keenly aware of the importance of keeping founders motivated, as they are instrumental to the success of the company. And they will interrogate the cap table to understand what value each entity brings to the table. At the same time, they realize that if active founders, and senior leadership does not have enough skin in the game, they will not remain motivated for the long run. It’s important to avoid situations where key stakeholders get diluted into oblivion.

![The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers by [Ben Horowitz]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51ZuUYAopiL.jpg)

![No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention by [Reed Hastings, Erin Meyer]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/414KRC8ts+L.jpg)